Manifestations: Remembering Brazilian Jazz Pianist and Composer Manfredo Fest

Four Decades of Innovation from a Bossa Pioneer

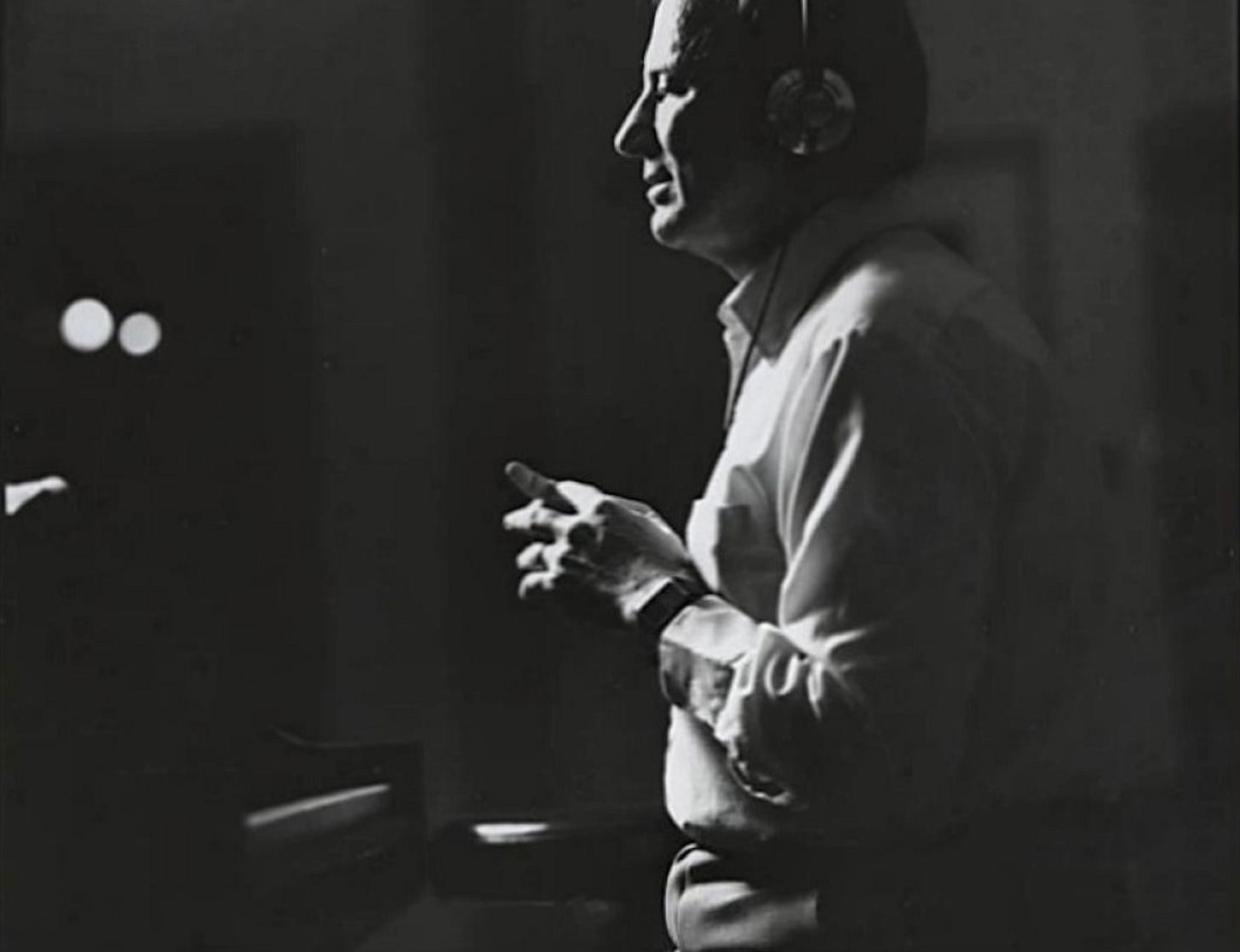

DMP Recording Artist Manfredo Fest, Promo Picture

Early Life and Education: Porto Alegre

Manfredo Fest (May 13, 1936 – October 8, 1999) was born legally blind in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil in 1936 to Adolfo Gustav Fest and Irma Berold. Fest was of German descent—his father was a concert pianist and conductor from Hanau who chaired the University of Porto Alegre's Music Department and taught piano at the university. Adolfo Fest studied with a student of Franz Liszt in Germany. In 1942 Manfredo was sent to the Santa Luzia School for the Blind in Porto Alegre. Fest was hit by a car when crossing the street in 1952, sustaining head injuries that resulted in permanent loss of hearing in his right ear and seventy percent loss in his left. From 1954-1957 Manfredo attended Colégio Nossa Senhora do Rosário in Porto Alegre, then went on to study music at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul from 1958-1961, where he learned to play keyboards and saxophone. In 1960 Manfredo married pianist and composer Lili Galiteri Fest, who taught Manfredo classical piano music from Bach to Chopin by transcribing each hand separately into Braille and learning four bars at a time.1 Manfredo had studied classical music with his father from age 5, but at 17 years old, he became interested in jazz pianists George Shearing and Bill Evans. While in college he gained steady work playing bossa nova in São Paulo.

“Manfredo was friends with Antonio Carlos Jobim and Joao Gilberto and Jobim considered him one of the foremost interpreters of his music.”

Early Career and Third Stream Fusion: São Paulo in the 1960s

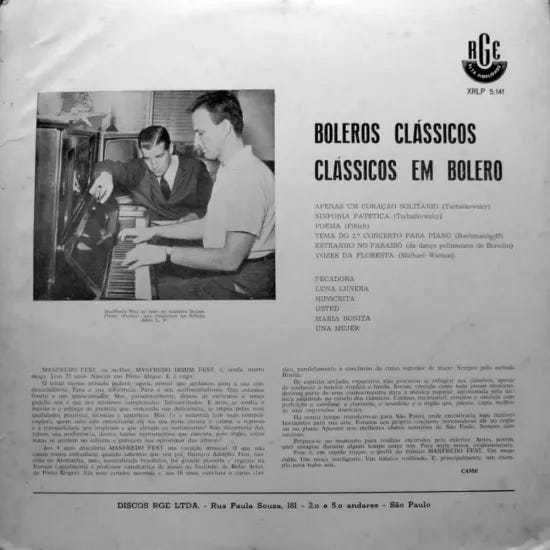

Fest began his musical career playing in bars, clubs and pubs in São Paulo with his jazz piano trio. Manfredo was "one of the better kept secrets among Brazil's bossa nova pioneers...Fest was part of the gathering of Brazilian musicians of the late-’50s who were developing the bossa nova movement.”2 Manfredo released his first album, Boleros Clássicos/Clássicos em Boleros in 1961 on the RGE label, showcasing both his classical and pop chops with a split program of classical masterpieces arranged in the bolero style, like Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony, and classic boleros like Maria Bonita. This album marks Fest’s first fusion of classical music and world elements. Fest would later specialize in “third stream” fusion of classical, Brazilian rhythms, and jazz improvisation, like his (unreleased) arrangement of Frederic Chopin’s Fantasy Impromptu in C-sharp minor, which cunningly combined the composer’s opening polyrhythmic flurry with rock-like bass and drums, then laid down a cool bossa groove for the melodic B section, finishing virtuosically with Manfredo’s own cadenza and the band rejoining on the Coda.

“Perhaps Fest was unique as one of the first Brazilian musicians to both record bossa nova and legitimately improvise like American jazz musicians in a modified post-bop style.”

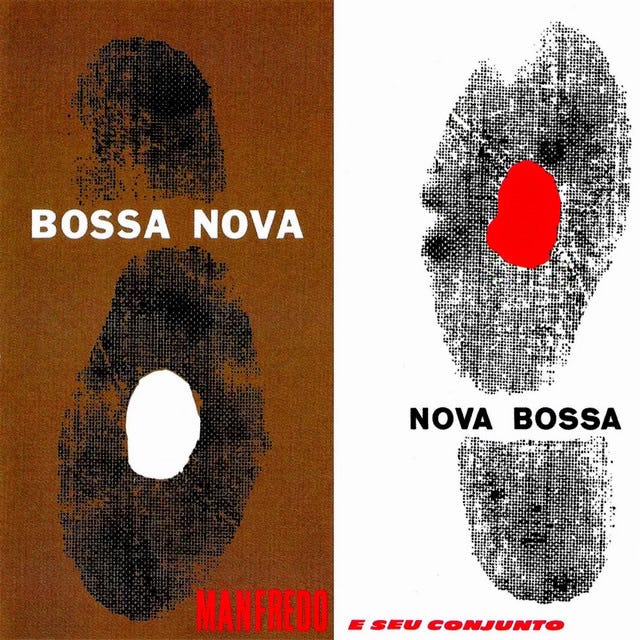

From 1963-1966, Manfredo recorded five albums as a leader, mostly on the RGE label. His first LP, Bossa Nova, Nova Bossa (1963), featured Humberto Clayber on bass, Antonio Pinheiro on drums and Hector Costita on saxophone and flute. Fest had already fully developed his mature signature sound, a very rhythmic blend of samba rhythms and jazz improvisation. Perhaps Fest was unique as one of the first Brazilian musicians to both record bossa nova and legitimately improvise like American jazz musicians in a modified post-bop style. During this time, Manfredo was friends with Antonio Carlos Jobim and Joao Gilberto and Jobim later considered him one of the foremost interpreters of his music.3

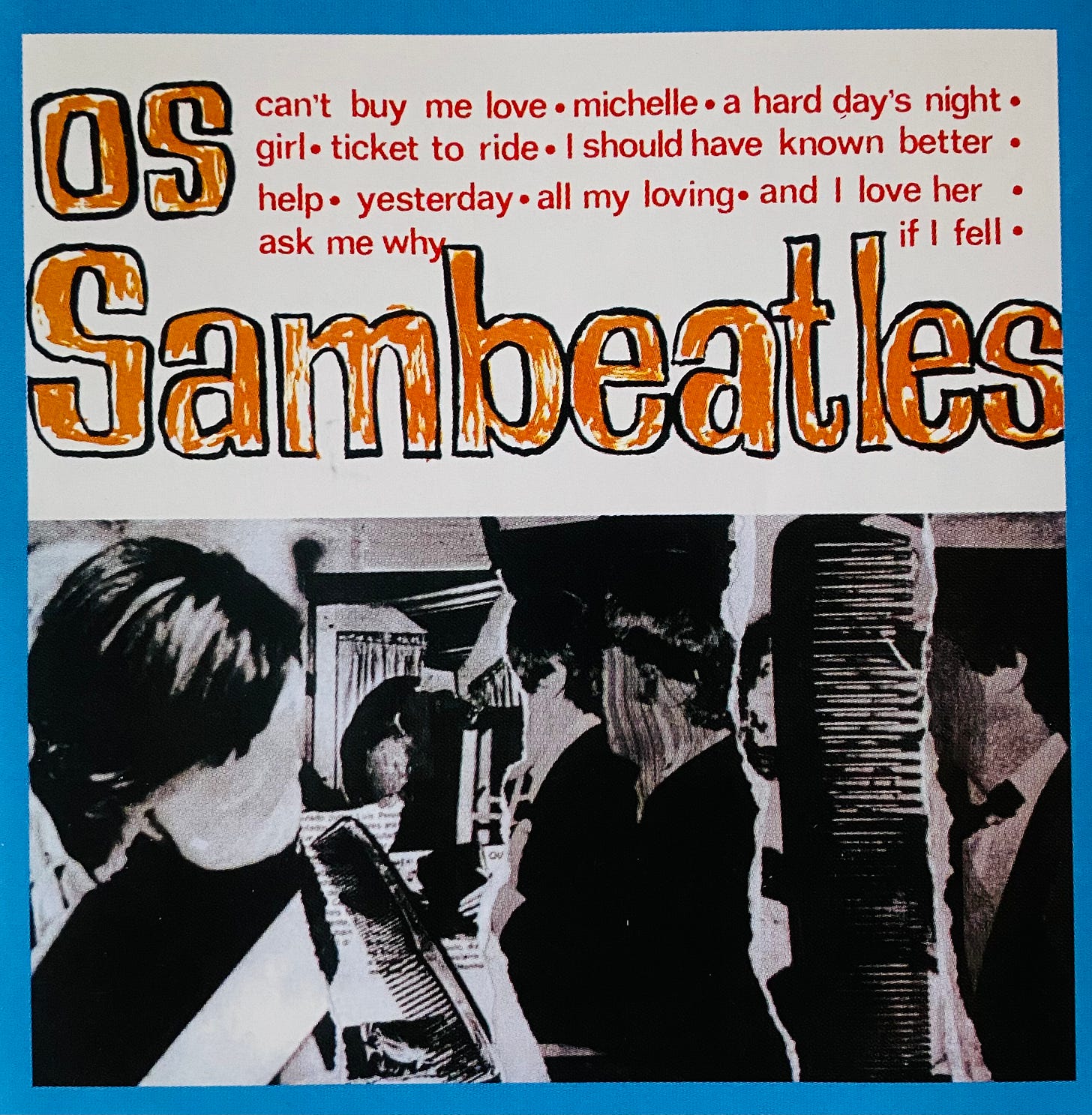

1966 saw Manfredo experimenting with Brazilian pop-rock hybrids on

Os Sambeatles (The Sambeatles), which combined crackling samba grooves with jazz and blues-drenched piano improvisations and refreshing, upbeat arrangements of popular songs like “Yesterday” and “A Hard Day’s Night.”

The 1970s: Bossa Nova and Fusion in America

In 1967 Manfredo moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota after getting recommended for a gig by Herb Schoenbaum, a Minneapolis radio personality who heard Manfredo play in Brazil. While working in the Twin Cities, Manfredo began a private jazz piano studio, earning a reputation for his pedagogical mastery of voicing in the style of Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson—and soon teaching these concepts to a young Maria Schneider. I can still hear Manfredo’s joyful rhythmic influence in her Grammy-winning big band compositions of the past few decades.

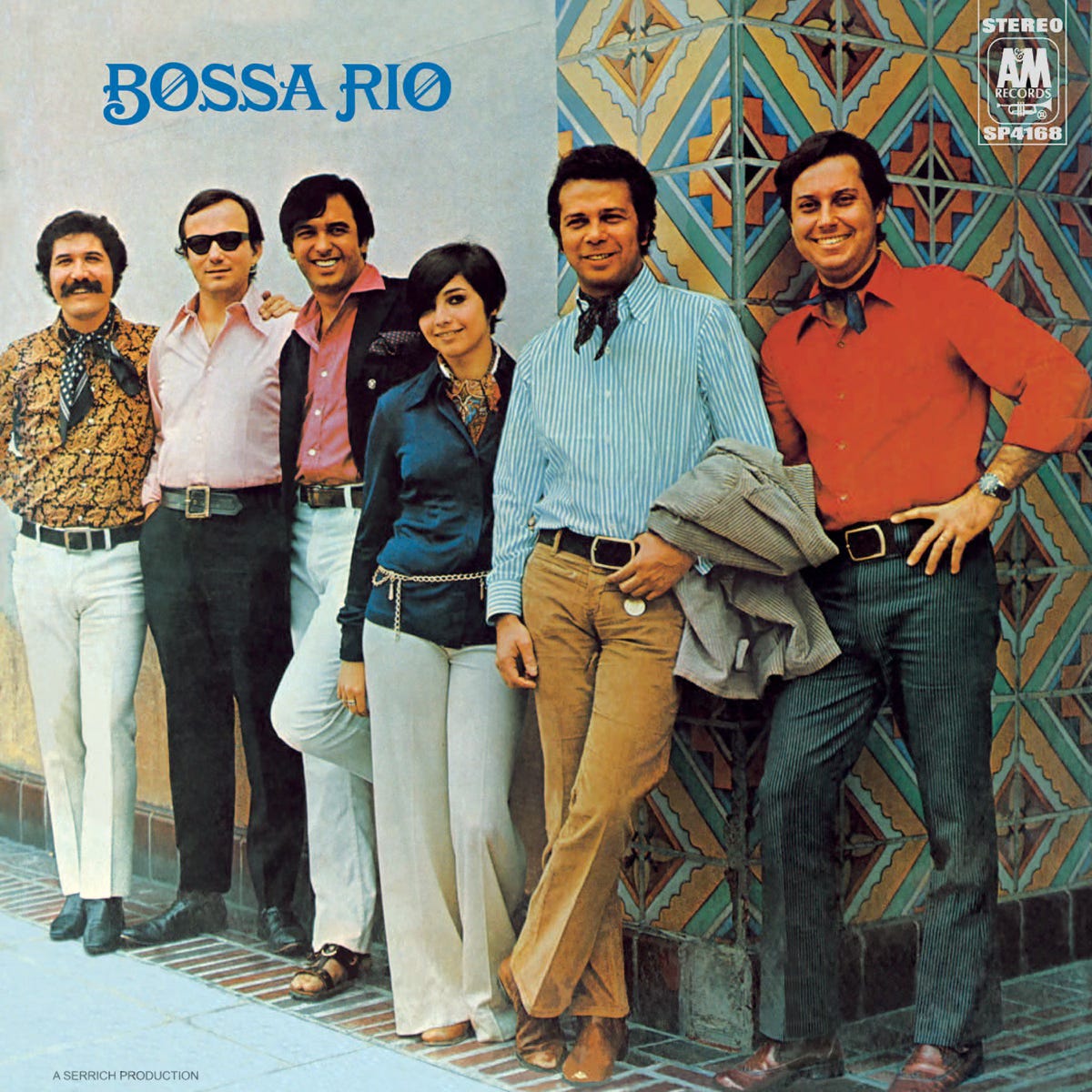

In the 1970s Manfredo moved to Los Angeles, during which time he worked with Sérgio Mendes as an arranger for Brazil ‘66, and both played keyboards and arranged for Mendes’ spin-off group Bossa Rio. His infectious and joyful arrangements for these popular groups connected with audiences around the world.

Manfredo’s 1976 album Brazilian Dorian Dream showcased the versatile pianist’s compositional side with the title track becoming Fest’s signature tune for the remainder of his career. “Brazilian Dorian Dream” cleverly combines a samba in 6/4 with a relentless Bach-inspired left hand ostinato figure in the A Dorian mode that breaks into acrobatic vocalise-doubled sequences on the bridge.

Fest’s first large budget album Manifestations (1979) was recorded in Hollywood, California with stars Lee Ritenour and Oscar Castro-Neves on guitar, Roberta Davis on vocals, and veteran arranger Bill Holman. Manfredo’s predilection for Brazilian-rock jazz fusion and third stream styles shines once again with “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” and “Bach’s Prelude and Fugue #2.”

The 1980s: Chicago and Collaborations

Fest then moved to Chicago and collaborated with Béla Fleck and the Flecktones founding member Howard Levy, with whom he wrote the song “Seresta.” It was in Chicago that Manfredo established a longtime working trio with Costa Rican drummer Alejo Poveda and New Zealander Thomas Kini on bass. While in the Windy City, Fest gigged at jazz clubs like The Green Mill, and recorded as a studio musician with Chicago voice-over artist Ken Nordine. He also found a friend in fellow blind jazz pianist George Shearing, who recorded Manfredo’s composition “That’s What She Says” on his 1980 album Blues Alley Jazz.

1987 saw the release of Braziliana (DMP), which featured Manfredo’s original composition by the same name that took the form of a mini-piano concerto combining rhythms and beats from various regions of Brazil with Fest’s signature melodic sequences.

In 1987 Manfredo moved to Palm Harbor, Florida to hone his craft in a climate that was more like home. “When I write my music, I always bring it to my Brazilian roots,” Manfredo shared with the Tampa Bay Times. He would go on to perform at the Clearwater Jazz Festival in 1989 and the Sarasota Jazz Festival in 1991.

“It’s important to have a ‘trademark.’ If I came to the United States to play American jazz, I’d be only one more in the crowd.”

—Manfredo Fest, 1997

The 1990s: Concord Jazz and Bossa Rebirth

“The fact that Manfredo Fest accomplished all of this in spite of his visual and auditory handicaps is an all but miraculous story of overcoming adversity to follow one’s dreams.”

In the early 1990s Manfredo signed with Concord Jazz, which began a series of releases that featured Manfredo’s Brazilian arrangements of jazz standards with well-known guest artists like Claudio Roditi, Hendrik Meurkens, Scott Hamilton, Portinho, and Cyro Baptista. The albums Oferenda (1993), Começar De Novo (1995), Fascinating Rhythm (1996), and Amazonas (1997) reintroduced Manfredo’s music to audiences around the world and helped cement his place as one of the few bossa nova pioneers to successfully merge his native music with American jazz while retaining the special characteristics of each unique style. Manfredo’s son Phill Fest played guitar on several of his Concord releases. Fest returned to DMP for what would be his final album, Just Jobim (1998).

The fact that Manfredo Fest accomplished all of this in spite of his visual and auditory handicaps is an all but miraculous story of overcoming adversity to follow one’s dreams. Fest died suddenly of liver failure at the age of 63 in Tampa, Florida.

I began studying remotely with Manfredo the last few years of his life using the unconventional method of tape-cassette lessons. He masterfully “spelled out” whatever Brazilian tune, jazz standard or original composition I requested to learn, one hand at a time. Manfredo would then improvise and give recommendations for scales and patterns that sounded best for the moment. I then transcribed everything he played on each lesson, which in hindsight was an excellent primer in ear training. What would unknowingly be the last of 28 lessons took place in person at Manfredo’s home on July 24, 1999, when he taught me the song Você e Eu—“You and I.”

My portrait of Manfredo in pencil from 2000

Phone interview with Lili Fest, July 7, 2015.

Phone interview with Lili Fest, July 7, 2015.