The Music of Middle Earth: Analyzing Andy Serkis' Character-Driven Melodies in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings Audiobooks

Celebrated Actor Brings New Life to Tolkien's Poetry Through In-Character Singing

Music holds a special place in J.R.R. Tolkien’s high fantasy world of Middle Earth. Even the creation myth at the opening of The Silmarillion tells of a universe born of divine interweaving musical themes. So it naturally follows that many of the characters in Tolkien’s masterwork The Lord of the Rings occasionally break out into song, sharing the tales and deeds of their ancient forefathers, or revealing their innermost thoughts and motivations in dramatic fashion.

This brief study of Andy Serkis’ memorable in-character singing from select examples and excerpts of Tolkien’s poetry in The Lord of The Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring reveals that the use of medieval musical modes and “heroic” intervals like the perfect fourth and fifth help create an immersive fantasy world in the trio of audiobooks published by HarperCollins in 2021.

As Bilbo Baggins, the halfling hero of The Hobbit, sets off on his final adventure, leaving the Shire and his precious ring behind for the elf kingdom of Rivendell, he begins to sing “in a low voice, as if to himself.”

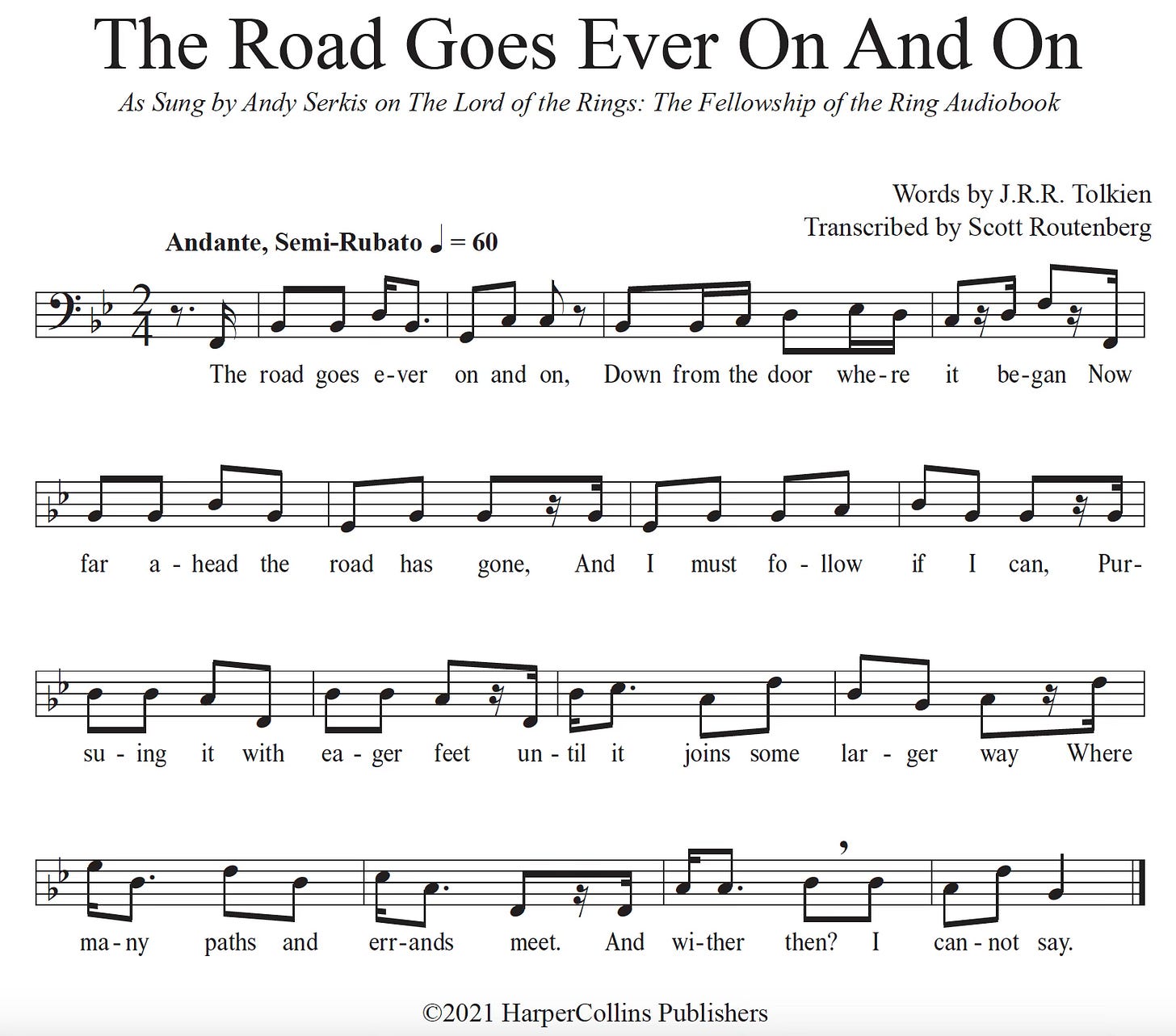

Andy Serkis’ melody, sung in the voice of Bilbo Baggins and sounding uncannily like Martin Freeman (who played Bilbo in the later Peter Jackson Hobbit trilogy), takes on a well-weathered, introspective character that does not stray from B-flat major, also known as the B-flat Ionian mode. Shire folk have much in common with turn-of-the-century rural English villagers, by Tolkien’s design, and the use of a plaintive major tune for this short poem “The Road Goes Ever On” makes it even easier for the listener to identify with the folksy old hobbit. Serkis sings the poem in his natural bass range, true to Tolkien’s description of “a low voice.” With a declamatory setting, the melody takes on an andante, or slow walking, tempo. There is much stepwise motion in the melody, and some skips, but the stars of the performance are the perfect fourth and fifth leaps at the opening “the road” and descending line “errands meet,” respectively. Serkis satisfies the phrase “as if to himself” by pacing the music in a semi-rubato manner, with short pauses, and taking on an introspective dynamic. He even cracks his voice in mild character-driven trepidation at the last line “and wither then? I cannot say.”

“Heroic characters have long been associated with perfect fifth intervals in programmatic music.”

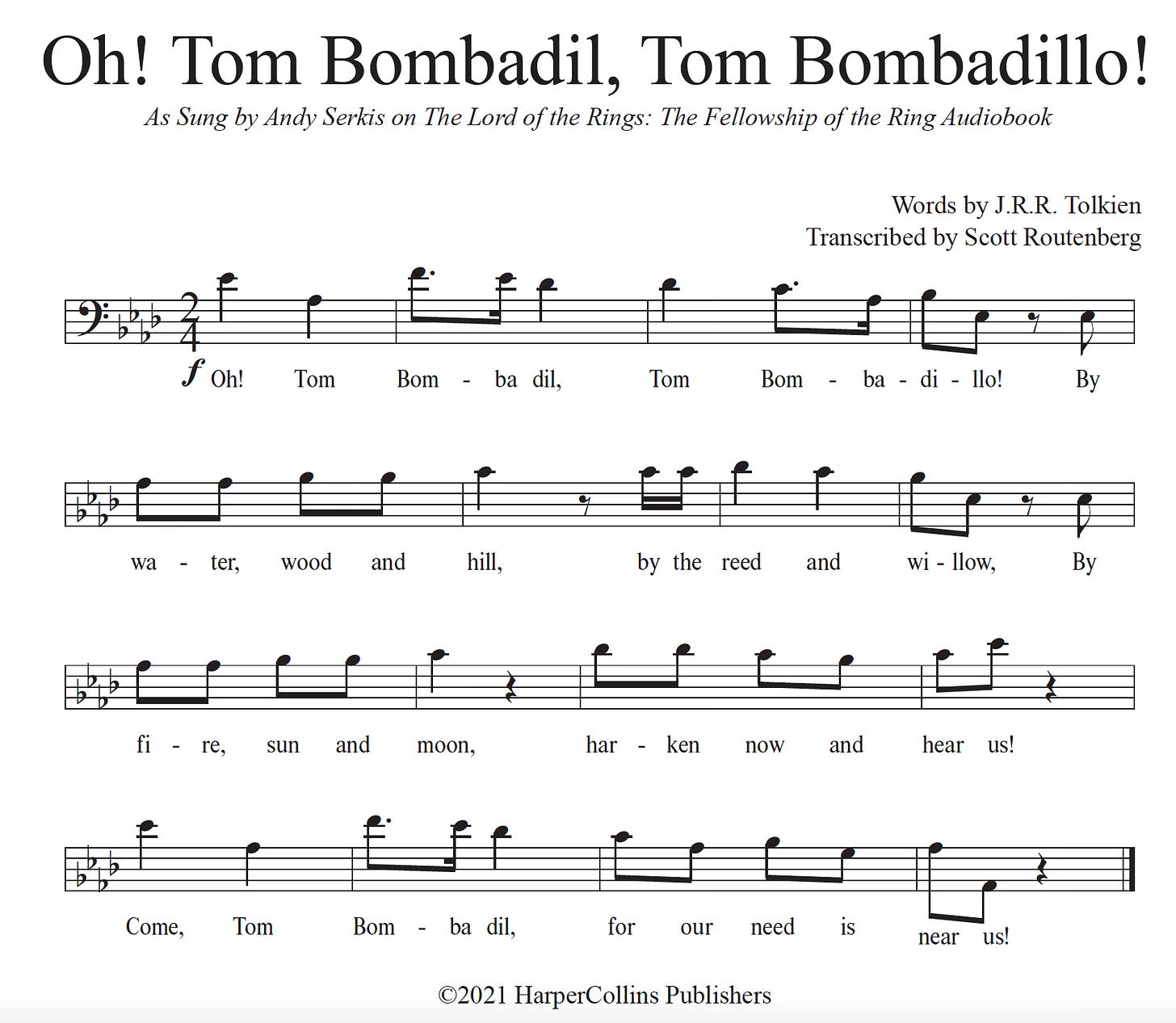

In the seventh chapter of the first book of The Fellowship of The Ring, the hobbits are rescued by a mysterious man named Tom Bombadil, who might be the oldest being in Middle Earth. Bombadil’s vivacious character speaks in sing-song nonsense rhymes, and Serkis interprets almost all of his lines in song, save Bombadil’s most serious thoughts and council. Arguably the most important of his rhymes is “Ho! Tom Bombadil, Tom Bombadillo,” which the hobbits must memorize if the need arises for Bombadil’s help once they leave his protected sylvan home (Bombadil goes on to rescue the hobbits from the shadowy barrow-wights after hearing Frodo sing his song).

Bombadil’s merry song is in the key of A-flat major and once again the notes do not stray from the Ionian mode, though the initial call “Oh! Tom Bombadil” implies the subdominant D-flat major before meandering through the dominant E-flat and then moving up the tonic A-flat major scale in ascending stepwise motion at the fifth measure’s “water, wood and hill.” The descending fifth leap at the beginning of Bombadil’s song helps to define his enigmatic character as a type of hero. Heroic characters have long been associated with perfect fifth intervals in programmatic music. Interestingly, Bombadil’s opening descending fifth is shared with the end of Bilbo Baggins’ song “The Road Goes Ever On and On.” The unexpected octave drop at the end of the song’s “near us” adds a touch of levity to Serkis’ Broadway-esque performance of Tom Bombadil, whose character was notably left out of Peter Jackson’s celebrated movie trilogy in the early 2000s.

“It is truly rare to hear a bass sing this low in any setting, and Serkis’ in-character performance as Gimli evokes the deep lore of the Dwarves’ ancient city.”

In chapter four, book two of The Fellowship of The Ring, “A Journey in the Dark,” the company winds their way through the labyrinthine Mines of Moria underneath the Misty Mountains, which was in days of old a majestic Dwarf kingdom called the Dwarrowdelf. Moved by the memory of the splendor of his forefathers’ realm, Gimli begins to sing “The World Was Young, The Mountains Green.”

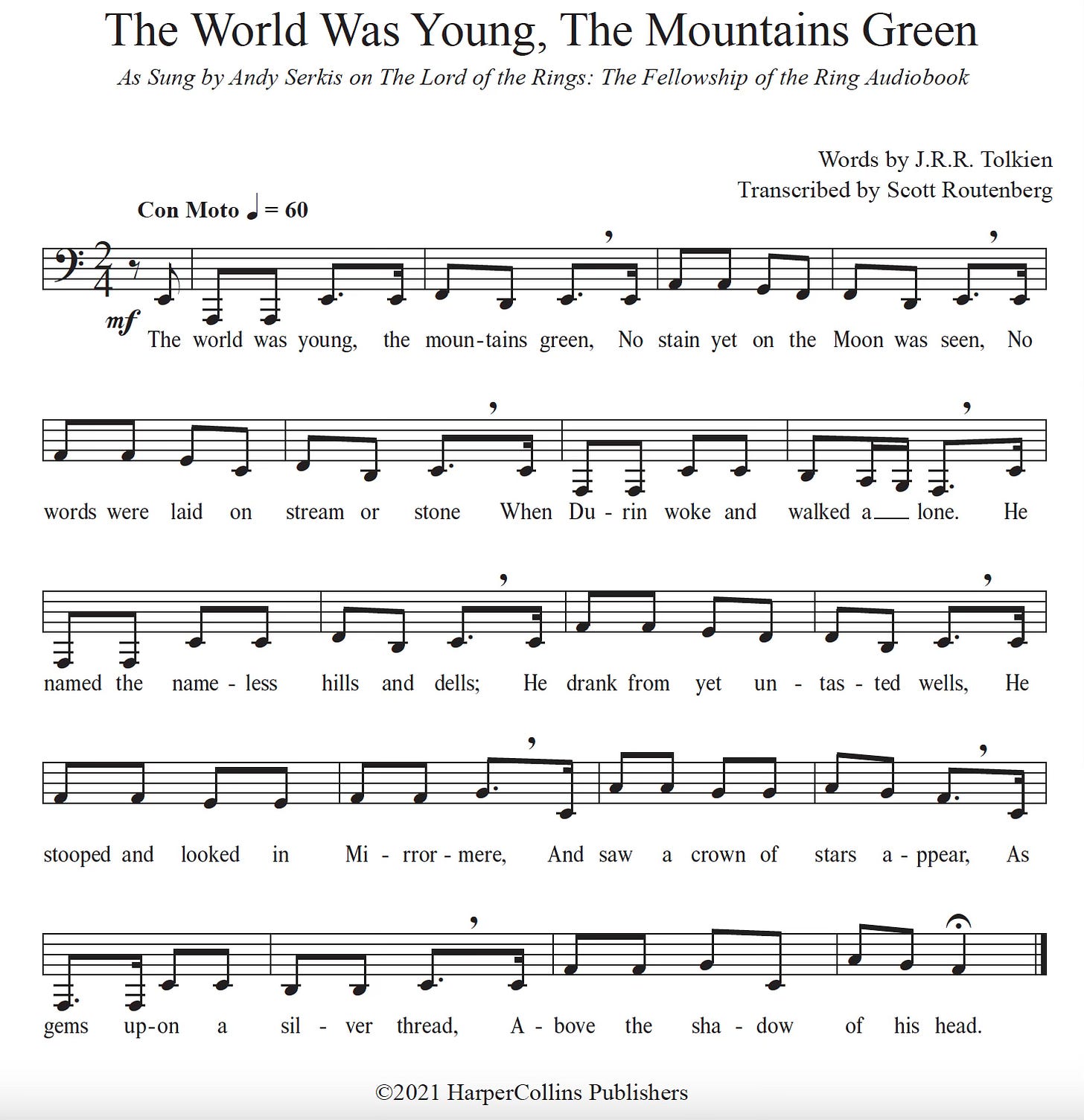

Serkis’ basso profundo range extends down to a low A in this poem and is chanted in “a deep voice,” true to Tolkien’s text. It is truly rare to hear a bass sing this low in any setting, and Serkis’ in-character performance as Gimli evokes the deep lore of the Dwarves’ ancient city. Similar to Tom Bombadil’s song, Serkis sings the first two notes of Gimli’s song as a descending perfect fifth, but in the lowest register of the voice, and from the fifth (E) to the tonic (A). As with Bilbo and Bombadil’s characters, the perfect fifth is prevalent in Gimli’s song, suggesting the heroism of the ancient race of the Dwarves.

The transcription of this melody is limited to an excerpt from the first stanza of the poem, but the melody repeats in successive stanzas. Serkis sings “The World Was Young, The Mountains Green” in the A Aeolian mode (natural minor), contrasting with the more upbeat major scale-based songs of Tom Bombadil and the hobbits. Text painting can be heard in measure eight when Serkis sings “walked alone” using descending stepwise motion from scale degree four to scale degree one, and again in measures 18-19 with a rising perfect fourth at the word “above.”

Andy Serkis’ reading of The Lord of The Rings is already notable due to his unique voicing of 132 different characters (including revisiting his famous voice of Gollum/Sméagol from Peter Jackson’s film trilogy); his memorable in-character song interpretations of Tolkien’s poetry in these audiobooks immerse the listener even further into the world of Middle Earth, and will likely captivate us for ages to come.

A special thank you to my wife Dr. Sofia Kraevska for listening to Andy Serkis’ performances and double checking the accuracy of my transcriptions.